Over the past few weeks, I've been working with some students on how to retell a text. What fun! But it's also given me the chance to think about how retelling is such an important foundation skill for summarizing. Here are some questions that I've been thinking about--and some of my partial answers.

Do readers need to be able to retell in order to write a good summary?

In general, I think that the answer is yes. Consider a student who reads a text and can't produce any ideas from the reading--or only a few scattered ideas, named out of order. Will that child be able to write a good summary? I doubt it. In order to select the most important ideas, a reader needs to be able to envision and work with most of the ideas from the text. Readers who have trouble recalling any ideas at all will flounder with the selection and synthesis that a summary requires.

This doesn't mean that kids who are struggling with retelling shouldn't be exposed to summarizing. In fourth grade, we don't have a moment to spare! But these readers will struggle with writing summaries on their own. Left to their own devices, they might fall into bad habits, like just copying sections of the text.

Instead, pull them into activities like choosing the best summary. Readers of all abilities can learn how to think about what makes a good summary. You could also try writing a group summary. Students provide the ideas or events, and you show them how to put them together into a summary. Another strategy that works well with struggling readers is sequencing events or information from the text. You give them the ideas (remember, this is the part that they struggle with), and they put the ideas in the order in which they appear in the text.

Are there any exceptions?

There are always exceptions, aren't there? That's what makes teaching reading so fun!

There is a small group of readers who will already be summarizing when you ask them to do a retelling. If you were to go by a retelling score alone (on the QRI or DRA), these readers might look like they are struggling. But the content of their retelling is markedly different from that of a struggling reader. When asked to retell, these readers may produce succinct versions of the text that put together ideas from various places into one nice neat package. Their "retellings" show an awareness of the main ideas of the text. (For example, if a student is retelling an episodic story, the student may collapse all of the episodes into one sentence.)

This is why scores and numbers don't tell the whole story. For these students, long and drawn out retellings are probably not necessary. They have already picked up the basics of summarizing by intuition. They would benefit from finding the best summary, sorting ideas as important or not important, and jumping into writing summaries.

Haven't I written about this before?

Um--yes. Quite a lot, as it happens. But with each new reader and new situation I find that I need to relearn and revisit what I already know. :)

Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Retelling (my book)

Previous posts

Retelling or Summarizing?

Summarizing a Story

Summarizing Fiction with Elephant and Piggie

What Should a Good Retelling Include?

Thursday, June 30, 2011

Saturday, June 25, 2011

Help for Word Callers: Changing Visual Images

Have you ever tried to open a can with a can opener, only to find that the cutting mechanism hasn't engaged? You can turn and turn the crank--but that can will never open. The opener is just sliding along the surface.

In a way, this is what reading is like for kids who don't attach meaning to the words in the text. They read and read, skimming along the surface. Yet they never dig into the text and open up the meaning.

Our job as teachers, then, is to help those little can openers engage! When I work with students who show this tendency, I try to think about how I can help the students to move below the surface of the text to open up the meaning.

Previously, I wrote about how teachers can use drawings to help readers make meaning from text, as well as how you can use manipulatives. Today's strategy is quite simple, and yet is very effective with students.

I first saw this in my son's kindergarten class. I'm sure that it has a proper name, and is probably written up in a book somewhere. If you know, please leave a comment.

The premise is simple: Take a sentence from the text that has visual imagery, but is somewhat ambiguous. Before showing students the text, share this sentence with them, and have students draw a picture to show the visual image that they create.

Here's how it worked with students. I was reading "Wings in the Water" with them, from the 2/3 Toolkit Texts book. I chose these sentences to share:

"A huge, flat creature leaps out of the sea. It skims over the water and flips backward with a splash."

The two boys who read the sentences started talking about it right away. What could it be? A penguin? They discarded this idea. One of them said, "I think I know what it is, but I don't know its name. Maybe it's a shark." The other pointed out that a shark really isn't flat. As they talked about these sentences, they were using all of the habits of successful reader--going back to the text (just the two sentences), looking at the meanings of words, trying to wring every single detail from the clues.

After a few moments, I gave them the text, which is about manta rays. "Oh! So that's what they're called," one of the boys said. I noticed the other one going back to his picture and drawing a manta ray. Skilled readers experience that visual flicker of a changing mental image all the time. For less skilled readers, it's a kind of new feeling. We paused a bit and talked about how their ideas of the text had changed. What was it about? Now that they were looking at pictures of the topic, how did they match up with the two sentences they had read?

Students who are word callers often don't dig around in sentences. With this activity, they have to look at each word and connect them to try to build some meaning. When they have built an idea, they may learn from looking at the text that they need to change their ideas--and this is okay. This is what skilled readers do all the time.

What I like most about this strategy is the simplicity of it. It doesn't require much preparation--just finding suitable sentences from the text, and coaching students through the process of drawing what they visualize. And yet the rewards can be worthwhile, getting students to engage with text and make new connections.

While it won't work for every text, it certainly is another good tool for helping students. One more thing to help open up those cans of meaning!

In a way, this is what reading is like for kids who don't attach meaning to the words in the text. They read and read, skimming along the surface. Yet they never dig into the text and open up the meaning.

Our job as teachers, then, is to help those little can openers engage! When I work with students who show this tendency, I try to think about how I can help the students to move below the surface of the text to open up the meaning.

Previously, I wrote about how teachers can use drawings to help readers make meaning from text, as well as how you can use manipulatives. Today's strategy is quite simple, and yet is very effective with students.

I first saw this in my son's kindergarten class. I'm sure that it has a proper name, and is probably written up in a book somewhere. If you know, please leave a comment.

The premise is simple: Take a sentence from the text that has visual imagery, but is somewhat ambiguous. Before showing students the text, share this sentence with them, and have students draw a picture to show the visual image that they create.

Here's how it worked with students. I was reading "Wings in the Water" with them, from the 2/3 Toolkit Texts book. I chose these sentences to share:

"A huge, flat creature leaps out of the sea. It skims over the water and flips backward with a splash."

The two boys who read the sentences started talking about it right away. What could it be? A penguin? They discarded this idea. One of them said, "I think I know what it is, but I don't know its name. Maybe it's a shark." The other pointed out that a shark really isn't flat. As they talked about these sentences, they were using all of the habits of successful reader--going back to the text (just the two sentences), looking at the meanings of words, trying to wring every single detail from the clues.

After a few moments, I gave them the text, which is about manta rays. "Oh! So that's what they're called," one of the boys said. I noticed the other one going back to his picture and drawing a manta ray. Skilled readers experience that visual flicker of a changing mental image all the time. For less skilled readers, it's a kind of new feeling. We paused a bit and talked about how their ideas of the text had changed. What was it about? Now that they were looking at pictures of the topic, how did they match up with the two sentences they had read?

| ||

| 100+ aquarium pictures, no rays. Oh well! |

What I like most about this strategy is the simplicity of it. It doesn't require much preparation--just finding suitable sentences from the text, and coaching students through the process of drawing what they visualize. And yet the rewards can be worthwhile, getting students to engage with text and make new connections.

While it won't work for every text, it certainly is another good tool for helping students. One more thing to help open up those cans of meaning!

Thursday, June 23, 2011

Open-Ended Responses

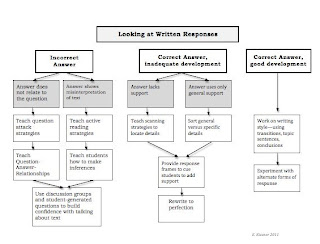

Today I had the privilege of presenting a workshop about helping students write open-ended responses. What an amazing group of teachers! I enjoyed meeting everyone and hearing about your classrooms and your schools.

When helping students to craft open-ended responses, it helps to look at the problems that students are having, and plan instruction from there.

Question-Answer-Relationships

For students who are having trouble answering the questions that are given, QARs can help. Here are some nice resources:

QAR posters and instructional materials

This is a great site with nicely formatted materials to print out and use right away.

QAR with pictures

I love this ReadWriteThink lesson that uses Question-Answer-Relationships with wordless books. Two of my favorites are used in the lesson plan--Zoom by Istvan Banyai and Tuesday by David Wiesner. By helping kids to find the answers to questions about pictures, this lesson helps students who may be struggling with finding answers in text.

Students who misinterpret text

These students are trying to make inferences and judgments about text, but are having difficulty. Often, it's helpful to work with these students on the skills of making inferences.

Using Schema to Make Inferences Powerpoint

I wrote this to guide students through the inference process.

Making Inferences

This is a presentation that I created for KSRA last year--it unpacks the skill of inferencing for teachers.

Inference Unit

This web page has many lessons and resources for teaching inferring.

Past Blog Posts about inferences

I write about inferences a lot!

Text Set for Making Inferences

Text-Based Inferences: Who's Talking?

Poetry Picture Books for Making Inferences

Literature Discussion Groups

Discussion groups can help kids of all ability levels to improve with answering questions and finding text details.

Literature Discussion Group Pack

This is a set of resources that I have on Slideshare.

Blog Posts

Lessons from Literature Circles

Discussion Groups: Getting Started

More information about inferences and helping kids to write open-ended responses--including sample texts--can be found in my book The Forest and the Trees.

I hope that these links are helpful! Please drop a comment about something that you like or plan to use.

When helping students to craft open-ended responses, it helps to look at the problems that students are having, and plan instruction from there.

Question-Answer-Relationships

For students who are having trouble answering the questions that are given, QARs can help. Here are some nice resources:

QAR posters and instructional materials

This is a great site with nicely formatted materials to print out and use right away.

QAR with pictures

I love this ReadWriteThink lesson that uses Question-Answer-Relationships with wordless books. Two of my favorites are used in the lesson plan--Zoom by Istvan Banyai and Tuesday by David Wiesner. By helping kids to find the answers to questions about pictures, this lesson helps students who may be struggling with finding answers in text.

Students who misinterpret text

These students are trying to make inferences and judgments about text, but are having difficulty. Often, it's helpful to work with these students on the skills of making inferences.

Using Schema to Make Inferences Powerpoint

I wrote this to guide students through the inference process.

Making Inferences

This is a presentation that I created for KSRA last year--it unpacks the skill of inferencing for teachers.

Inference Unit

This web page has many lessons and resources for teaching inferring.

Past Blog Posts about inferences

I write about inferences a lot!

Text Set for Making Inferences

Text-Based Inferences: Who's Talking?

Poetry Picture Books for Making Inferences

Literature Discussion Groups

Discussion groups can help kids of all ability levels to improve with answering questions and finding text details.

Literature Discussion Group Pack

This is a set of resources that I have on Slideshare.

Blog Posts

Lessons from Literature Circles

Discussion Groups: Getting Started

More information about inferences and helping kids to write open-ended responses--including sample texts--can be found in my book The Forest and the Trees.

I hope that these links are helpful! Please drop a comment about something that you like or plan to use.

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

Solving the Retelling Problem, Part 2

My youngest son can turn anything into a story. In the grocery store, he would take anything at hand--sponges, pasta boxes, cans of soup--and start making them talk to each other. Stories in our house are told and retold, lengthened and shortened, acted out and rewritten.

This makes it difficult for me to coach some students through retelling. The shorthand, private speech of my everyday life just doesn't translate at first for some kids. To me, using figures to act out a story is second nature. But this needs to be taught to some kids.

For example, take a recent retelling session with a struggling reader. I was taking on most of the work in our retelling of Anansi and the Talking Watermelon; he was just moving around the figures and filling in some events.

"'Then Anansi tricked Possum into thinking that watermelons can talk,'" I read from our list of events. "Can you show this event with your figures?"

The student picked up Possum, Anansi, and the watermelon, and made some mumbling sounds, like fake talking.

This wasn't quite what I was looking for. "Could you act this event out with your figures?" I asked.

"I don't know what they say," he replied.

Oh! I probably would have just picked up Possum and had him say something along the lines of, "Oh, look, an amazing talking watermelon." But this student couldn't get from our events to this level of imagination.

Here was an opportunity to direct the student back to the text. It took awhile, but we looked at what was in the text and eventually got that Possum to talk. I think that this is crucial to retelling--that kids move the figures smoothly along from event to event, being able to show what's happening and engaging in some little addition that collapse the events in the text. ("A talking watermelon? Cool!")

I was kind of worried about the whole interaction, but I felt vindicated when we got to the end. King Bear throws the watermelon, which cracks, and then Anansi is freed. The student showed the watermelon flying in the air, and then said, "Freedom!" He looked at me and laughed. "That's what Anansi would say, 'cause now he can get out."

These are the kinds of comments that show me that retelling is working. To be able to add little bits of dialogue, make the characters talk to each other--this shows an understanding of the story. Something is happening. We still have a long way to go to retelling independence. But these little moments show that we are making progress.

It's not quite at the level of talking sponges and fighting soup cans, but it's a start.

This makes it difficult for me to coach some students through retelling. The shorthand, private speech of my everyday life just doesn't translate at first for some kids. To me, using figures to act out a story is second nature. But this needs to be taught to some kids.

For example, take a recent retelling session with a struggling reader. I was taking on most of the work in our retelling of Anansi and the Talking Watermelon; he was just moving around the figures and filling in some events.

"'Then Anansi tricked Possum into thinking that watermelons can talk,'" I read from our list of events. "Can you show this event with your figures?"

The student picked up Possum, Anansi, and the watermelon, and made some mumbling sounds, like fake talking.

This wasn't quite what I was looking for. "Could you act this event out with your figures?" I asked.

"I don't know what they say," he replied.

Oh! I probably would have just picked up Possum and had him say something along the lines of, "Oh, look, an amazing talking watermelon." But this student couldn't get from our events to this level of imagination.

Here was an opportunity to direct the student back to the text. It took awhile, but we looked at what was in the text and eventually got that Possum to talk. I think that this is crucial to retelling--that kids move the figures smoothly along from event to event, being able to show what's happening and engaging in some little addition that collapse the events in the text. ("A talking watermelon? Cool!")

I was kind of worried about the whole interaction, but I felt vindicated when we got to the end. King Bear throws the watermelon, which cracks, and then Anansi is freed. The student showed the watermelon flying in the air, and then said, "Freedom!" He looked at me and laughed. "That's what Anansi would say, 'cause now he can get out."

These are the kinds of comments that show me that retelling is working. To be able to add little bits of dialogue, make the characters talk to each other--this shows an understanding of the story. Something is happening. We still have a long way to go to retelling independence. But these little moments show that we are making progress.

It's not quite at the level of talking sponges and fighting soup cans, but it's a start.

Monday, June 20, 2011

Solving the Retelling Problem

It happens at the start of every school year--at least three or four students in my class can't retell. They'll dutifully chug along in a piece, reading every word. When I say, "Could you please retell what happened in the passage?" I'll get--nothing.

Or almost nothing. Sometimes these kids will produce a few sentences, sometimes a backwards account of the story. But the retellings are not quite what I hope to see in fourth grade. With summarizing on the horizon, we need to get retelling taken care of quickly! I think that kids need to be able to retell a story confidently before we can accomplish much with summarizing.

Here are some strategies that I like to use to start with.

Sequence events from the story: Working with a fairly short story (the ones in Highlights work well), I put the events from the story on notecards or strips of paper. After the student reads the story, the student puts the events back together in the proper sequence.

Why it's useful: Kids who struggle with retelling often have trouble with putting ideas from a text into their own words. This activity models paraphrasing. In addition, this helps students to review the sequential nature of a narrative.

Good for the whole class? Yes, with modifications. For kids who are not struggling with retelling, you can challenge them to sequence the events, and then decide which are important or not important.

Link to plot interactive with events

http://www.learner.org/interactives/story/sequence.html

Retell with figures: Using pictures or objects to retell can help a student to match events to characters and objects. Give students a set of pictures that go along with a story that they are reading. As they learn the process, they can create their own pictures and figures.

Why it's useful: You can't act out what you don't understand. When kids have to show the action, they are much more likely to build those bridging inferences that help them create and clarify meaning. One of my favorite parts of the retelling lesson is when kids make those realizations--"Oh, so that's why this happened!"

Good for the whole class? Yes! Everyone can benefit from retelling with figures--and have fun doing it.

Link to story with retelling figures

http://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Summarizing-Stories-216952

Retelling frame: Some kids benefit from a reminder sheet about what to include in a retelling. You can use a story map to help students think of the characters, setting, problem, and solution, or your own frame that includes specific parts of the story for your classroom.

Why it's useful: The frame helps students to internalize the important elements of a retelling.

Good for the whole class? This is one that I save for the students who are struggling. The sooner the kids can retell on their own, the better.

Link to SomebodyWanted-But-So graphic organizer

http://wvde.state.wv.us/strategybank/Somebody-Wanted-But-So.html

While these don't produce instant results, with time I see some improvement in retelling. What have you found that works well for you and your students?

Or almost nothing. Sometimes these kids will produce a few sentences, sometimes a backwards account of the story. But the retellings are not quite what I hope to see in fourth grade. With summarizing on the horizon, we need to get retelling taken care of quickly! I think that kids need to be able to retell a story confidently before we can accomplish much with summarizing.

Here are some strategies that I like to use to start with.

Sequence events from the story: Working with a fairly short story (the ones in Highlights work well), I put the events from the story on notecards or strips of paper. After the student reads the story, the student puts the events back together in the proper sequence.

Why it's useful: Kids who struggle with retelling often have trouble with putting ideas from a text into their own words. This activity models paraphrasing. In addition, this helps students to review the sequential nature of a narrative.

Good for the whole class? Yes, with modifications. For kids who are not struggling with retelling, you can challenge them to sequence the events, and then decide which are important or not important.

Link to plot interactive with events

http://www.learner.org/interactives/story/sequence.html

Retell with figures: Using pictures or objects to retell can help a student to match events to characters and objects. Give students a set of pictures that go along with a story that they are reading. As they learn the process, they can create their own pictures and figures.

Why it's useful: You can't act out what you don't understand. When kids have to show the action, they are much more likely to build those bridging inferences that help them create and clarify meaning. One of my favorite parts of the retelling lesson is when kids make those realizations--"Oh, so that's why this happened!"

Good for the whole class? Yes! Everyone can benefit from retelling with figures--and have fun doing it.

Link to story with retelling figures

http://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Summarizing-Stories-216952

Retelling frame: Some kids benefit from a reminder sheet about what to include in a retelling. You can use a story map to help students think of the characters, setting, problem, and solution, or your own frame that includes specific parts of the story for your classroom.

Why it's useful: The frame helps students to internalize the important elements of a retelling.

Good for the whole class? This is one that I save for the students who are struggling. The sooner the kids can retell on their own, the better.

Link to SomebodyWanted-But-So graphic organizer

http://wvde.state.wv.us/strategybank/Somebody-Wanted-But-So.html

While these don't produce instant results, with time I see some improvement in retelling. What have you found that works well for you and your students?

Saturday, June 18, 2011

Multiple Literacies

I had such a wonderful time at Friday's workshop--thank you to everyone who attended! As promised, here are the links to more information about multiple literacies.

This is a nice introduction to multiple literacies:

http://www.drawingwriting.com/multlit.html

This site includes links to videos with teachers explaining how they use multiple literacies in the classroom:

http://faculty.uoit.ca/hughes/Contexts/MultipleLiteracies.html

Here is a discussion of how to use visual literacy in the classroom:

http://k-8visual.info/whatis_Text.html

During the workshop, we looked at how readers process information that is composed of both images and text. I love the Elephant and Piggie books for this--they are an easy introduction to reading pictures. Older students enjoy Calvin and Hobbes. The story doesn't live in the pictures or the print--it exists in the combination of the two.

"Re-composing" means taking information from one modality and transferring it to another. This is a great reading activity, as it requires students to integrate ideas. Last school year, I wrote about how students can do this to build summarizing skills. But re-composing doesn't have to be a formal lesson. On a visit to South Middleton Park last night, my youngest son and I re-composed some of the signs that were posted around the park, putting the information from the pictures into words. (The sign about how dogs must be leashed and cleaned up after was particularly funny!)

Reading visual texts is not necessarily easier than reading print--instead, it requires a different set of skills. Modeling your own thinking as a reader interacting with these texts is an important way to help kids understand how to integrate pictures with text. For our readers who struggle with both decoding and language comprehension, visual texts can be a pathway to helping them to understand making inferences and summarizing stories.

Here is a collection of links related to graphic novels, visual literacy, and multiple literacies.

Graphic Novels in the Classroom (teacher blog)

http://classroomcomics.wordpress.com/category/classroom-practice/

Cartoons for the Classroom

http://nieonline.com/aaec/cftc.cfm

Graphic Novels for (Really) Young Readers (includes a list of suggested titles)

http://www.schoollibraryjournal.com/article/CA6312463.html

The Comic Book Project

http://www.comicbookproject.org/index.html

This is a nice introduction to multiple literacies:

http://www.drawingwriting.com/multlit.html

This site includes links to videos with teachers explaining how they use multiple literacies in the classroom:

http://faculty.uoit.ca/hughes/Contexts/MultipleLiteracies.html

Here is a discussion of how to use visual literacy in the classroom:

http://k-8visual.info/whatis_Text.html

During the workshop, we looked at how readers process information that is composed of both images and text. I love the Elephant and Piggie books for this--they are an easy introduction to reading pictures. Older students enjoy Calvin and Hobbes. The story doesn't live in the pictures or the print--it exists in the combination of the two.

"Re-composing" means taking information from one modality and transferring it to another. This is a great reading activity, as it requires students to integrate ideas. Last school year, I wrote about how students can do this to build summarizing skills. But re-composing doesn't have to be a formal lesson. On a visit to South Middleton Park last night, my youngest son and I re-composed some of the signs that were posted around the park, putting the information from the pictures into words. (The sign about how dogs must be leashed and cleaned up after was particularly funny!)

Reading visual texts is not necessarily easier than reading print--instead, it requires a different set of skills. Modeling your own thinking as a reader interacting with these texts is an important way to help kids understand how to integrate pictures with text. For our readers who struggle with both decoding and language comprehension, visual texts can be a pathway to helping them to understand making inferences and summarizing stories.

Here is a collection of links related to graphic novels, visual literacy, and multiple literacies.

Graphic Novels in the Classroom (teacher blog)

http://classroomcomics.wordpress.com/category/classroom-practice/

Cartoons for the Classroom

http://nieonline.com/aaec/cftc.cfm

Graphic Novels for (Really) Young Readers (includes a list of suggested titles)

http://www.schoollibraryjournal.com/article/CA6312463.html

The Comic Book Project

http://www.comicbookproject.org/index.html

Friday, June 17, 2011

Intertextuality

This is a term that I've been hearing more and more of lately. At first I discounted it as something that is beyond my students. But the more that I learned about intertextuality, the more that I realized that it is relevant and important for all readers--and pretty fun, also.

What is intertextuality? Simply put, it's the way that readers can make connections between texts. But intertextuality is more than making a chart to compare texts. When we think intertextually, we look for components that go across texts. When my youngest son looks at the Elephant and Piggie books to find the pigeon that Mo Willems puts on the last pages, that's intertextual thinking. When my older son talks about the differences between Egyptian and Greek mythology (as expressed in Rick Riordan's books), that's intertextual thinking. Intertextual thinking can also be looking at patterns of events across stories, or looking at how authors have chosen to convey ideas about the same topic in different ways.

Here is a more exhaustive description of intertextuality:

http://thinkingtesolteacher.wikispaces.com/Intertextuality

If you prefer learning through video, you may enjoy this:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6BFeVWb8vc

Intertextuality is really nothing new--it's just giving a name to what's been there all along. But the importance of intertextual thinking means that our readers need to have access to some of the big stories and themes. This year, I'll be thinking about how to equip students with the background knowledge they need to make these intertextual connections.

In the Common Core Standards, fourth graders are expected to "Compare and contrast the treatment of similar themes and topics (e.g., opposition of good and evil) and patterns of events (e.g., the quest) in stories, myths, and traditional literature from different cultures." This is a lot different from the "find one similarity and two differences" that has been the expectation up to now. I'll be doing a lot of thinking about how to build this into my next school year!

Other posts about comparing texts and intertextual thinking:

Comparing Texts

Comparing Texts: Narrative and Blog

What is intertextuality? Simply put, it's the way that readers can make connections between texts. But intertextuality is more than making a chart to compare texts. When we think intertextually, we look for components that go across texts. When my youngest son looks at the Elephant and Piggie books to find the pigeon that Mo Willems puts on the last pages, that's intertextual thinking. When my older son talks about the differences between Egyptian and Greek mythology (as expressed in Rick Riordan's books), that's intertextual thinking. Intertextual thinking can also be looking at patterns of events across stories, or looking at how authors have chosen to convey ideas about the same topic in different ways.

Here is a more exhaustive description of intertextuality:

http://thinkingtesolteacher.wikispaces.com/Intertextuality

If you prefer learning through video, you may enjoy this:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P6BFeVWb8vc

Intertextuality is really nothing new--it's just giving a name to what's been there all along. But the importance of intertextual thinking means that our readers need to have access to some of the big stories and themes. This year, I'll be thinking about how to equip students with the background knowledge they need to make these intertextual connections.

In the Common Core Standards, fourth graders are expected to "Compare and contrast the treatment of similar themes and topics (e.g., opposition of good and evil) and patterns of events (e.g., the quest) in stories, myths, and traditional literature from different cultures." This is a lot different from the "find one similarity and two differences" that has been the expectation up to now. I'll be doing a lot of thinking about how to build this into my next school year!

Other posts about comparing texts and intertextual thinking:

Comparing Texts

Comparing Texts: Narrative and Blog

Sunday, June 12, 2011

Adding Richness to Grammar Instruction

I've always had a love/hate relationship with grammar lessons. In my own life, I really love grammar. I love the way that one word can change an entire sentence, the way that punctuation has evolved over time (and is still evolving!) and the way that words have entered our language.

But it's never been easy to communicate this love of grammar in the classroom. Few fourth graders really want to hear about how the word sports really is related to import. And not many are up for a discussion about how the rules for commas in a series differ across countries. There are also the practical issues of where to fit in grammar and how to connect it to everything else.

Of course, it's easy for people who are outside of the classroom to say that grammar fits in everywhere. And it does--in a way. It's easy for me to talk about grammar all the time. But for my talking to translate into actual learning, I need to take the time for more formal planning. Just try to get fourth graders to write sentences with adverbial phrases!

While I haven't completely solved the grammar problem, I have developed a general formula that gets me through.

Link to academic vocabulary: This satisfies my desire to talk about new and interesting words. Instead of teaching students with how the word comma entered the language, however, I try to pull out an academic word that links to the grammar content. When I taught about commas in a series, however, it worked perfectly to teach the word series. We looked at how they already know this word (World Series, television series) and connected it to new meanings.

Silly writing: With fourth graders, I have to keep things light and playful. For teaching about commas in a series, I drew some silly pictures and asked kids to write sentences about them. For example, next to a picture of a monster, the question was, "What are this monster's favorite foods?" These kinds of questions provide lots of practice, but are still interesting and engaging. (And kids love teacher-illustrated pages, even when the illustrations are not the best.)

Fun interactives: Grammar is something that lends itself well to computer games. For commas, I found this great interactive site. These sites are a big improvement on the dreadful workbook pages I did as a child! I do make sure that I go through every site, of course, to make sure that the rules in the site are the same as what I am teaching.

Flexibility in rules: I've decided that it's not confusing to students if I show them examples of how usage might be different in different situations. Kids need to see this--in fact, it's more confusing to not address this issue. When we were looking at commas, I found examples of how some writers do not use the comma before the and. When I teach capitalization next year, I'm going to actively seek examples of the changing usage of capitalization.

Real writing application: This is the hardest part, but also the most important. When we were working on commas, students wrote pages for a book about our field trip. Each page included a series of items that we saw or did on the trip. When the book was put together, we had the story of our field trip.

But it's never been easy to communicate this love of grammar in the classroom. Few fourth graders really want to hear about how the word sports really is related to import. And not many are up for a discussion about how the rules for commas in a series differ across countries. There are also the practical issues of where to fit in grammar and how to connect it to everything else.

Of course, it's easy for people who are outside of the classroom to say that grammar fits in everywhere. And it does--in a way. It's easy for me to talk about grammar all the time. But for my talking to translate into actual learning, I need to take the time for more formal planning. Just try to get fourth graders to write sentences with adverbial phrases!

While I haven't completely solved the grammar problem, I have developed a general formula that gets me through.

Link to academic vocabulary: This satisfies my desire to talk about new and interesting words. Instead of teaching students with how the word comma entered the language, however, I try to pull out an academic word that links to the grammar content. When I taught about commas in a series, however, it worked perfectly to teach the word series. We looked at how they already know this word (World Series, television series) and connected it to new meanings.

Silly writing: With fourth graders, I have to keep things light and playful. For teaching about commas in a series, I drew some silly pictures and asked kids to write sentences about them. For example, next to a picture of a monster, the question was, "What are this monster's favorite foods?" These kinds of questions provide lots of practice, but are still interesting and engaging. (And kids love teacher-illustrated pages, even when the illustrations are not the best.)

Fun interactives: Grammar is something that lends itself well to computer games. For commas, I found this great interactive site. These sites are a big improvement on the dreadful workbook pages I did as a child! I do make sure that I go through every site, of course, to make sure that the rules in the site are the same as what I am teaching.

Flexibility in rules: I've decided that it's not confusing to students if I show them examples of how usage might be different in different situations. Kids need to see this--in fact, it's more confusing to not address this issue. When we were looking at commas, I found examples of how some writers do not use the comma before the and. When I teach capitalization next year, I'm going to actively seek examples of the changing usage of capitalization.

Real writing application: This is the hardest part, but also the most important. When we were working on commas, students wrote pages for a book about our field trip. Each page included a series of items that we saw or did on the trip. When the book was put together, we had the story of our field trip.

Thursday, June 9, 2011

Text Structure Picture Books: Owen and Mzee

Now that the school year is over, I'm reading to a very demanding young critic--my youngest son, who will be entering first grade. He is currently in an animal loving phase, which means that I'm combing the library shelves for anything that has to do with big cats, snakes, or African wildlife. His desire for information outpaces his independent reading ability...which means that I've been reading aloud a lot of expository text.

As I read many texts that deal with the same topics, it's interesting to see how different authors faced the challenge of writing for younger readers--how they organize information, how they explain ideas, how they keep sentences short.

One of my recent favorites is Owen and Mzee: The Language of Friendship. This is on my list for a read aloud or shared reading with the document camera. You've probably heard the story--a young hippo named Owen becomes friends with a formerly grumpy tortoise named Mzee. (You can find out more at the website.)

What makes the book such a great read is the way that the authors harness and use text structures throughout the book. At the beginning, Owen's arrival at Haller Park is explained through cause and effect. A chronological order structure continues as Owen's friendship with Mzee is explained.

My favorite part is at the end. As I've written before, compare and contrast text structure is sometimes difficult to find in the wilds of real text. But there is a wonderful page that explains why Owen is not acting like a regular hippo. The authors compare and contrast Owen's behavior with that of typical hippos. Then this whole comparison becomes the problem for a problem/solution part of text. It's an easy introduction to the way that authors use multiple text structures to explain ideas.

As I look at books for the next school year, I want to find books that use academic patterns and structures, but have accessible topics. Kids who don't have their own personal readers at home are often unfamiliar with the way that expository text sounds. By finding lots of read alouds, I can help students to learn more about this kind of text.

As I read many texts that deal with the same topics, it's interesting to see how different authors faced the challenge of writing for younger readers--how they organize information, how they explain ideas, how they keep sentences short.

One of my recent favorites is Owen and Mzee: The Language of Friendship. This is on my list for a read aloud or shared reading with the document camera. You've probably heard the story--a young hippo named Owen becomes friends with a formerly grumpy tortoise named Mzee. (You can find out more at the website.)

What makes the book such a great read is the way that the authors harness and use text structures throughout the book. At the beginning, Owen's arrival at Haller Park is explained through cause and effect. A chronological order structure continues as Owen's friendship with Mzee is explained.

My favorite part is at the end. As I've written before, compare and contrast text structure is sometimes difficult to find in the wilds of real text. But there is a wonderful page that explains why Owen is not acting like a regular hippo. The authors compare and contrast Owen's behavior with that of typical hippos. Then this whole comparison becomes the problem for a problem/solution part of text. It's an easy introduction to the way that authors use multiple text structures to explain ideas.

As I look at books for the next school year, I want to find books that use academic patterns and structures, but have accessible topics. Kids who don't have their own personal readers at home are often unfamiliar with the way that expository text sounds. By finding lots of read alouds, I can help students to learn more about this kind of text.

Labels:

compare and contrast,

picture books,

text structure

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)