I've updated the Topics and Main Ideas PowerPoint that was previously on Slideshare. It covers finding the topic of a text, looking at multiple referents, and finding main ideas.

You can view it at Slideshare, or download the updated version at TeachersPayTeachers.

Thursday, December 27, 2012

Thursday, December 13, 2012

Going back, back, back to the text

This year, I'm really focusing on helping my readers to return to the text to find answers. Intermediate readers often have a once and done philosophy--"I've read it, I'm done, let's move on." But returning to the text is often essential for deeper reading and thinking tasks.

How does this skill develop? Like summarizing, it's not something that we can just tell students to do. There are two main ways to help students learn to return to the text. The first way is to help them navigate through a text, so that they realize they can find answers efficiently. The second way is to give readers meaningful literal tasks that require them to return to the text.

Navigating a text

As soon as we start with nonfiction, I coach students to find their way through a text. At first, this is very directed. "Put your fingers on the second heading," I'll say, or "Use your pencil point to touch the third paragraph under the first heading. What word do you see?" It's easy for me to see who is using the headings and who is not.

After a first silent read of a text, I also like to have readers partner-read a text by sentence. Many struggling readers do not notice sentence and paragraph boundaries. When they read sentence-by-sentence, these boundaries matter! "Hey, it's my turn!" a partner will say indignantly.

What if you only have texts that don't have headings? Use different texts for instruction. For example, many popular Seymour Simon books have neither headings nor page numbers nor captions. These are fine to have in my classroom library, but not very useful for instruction. It takes a long time just to get everyone (literally) on the same page.

Finding words in a text

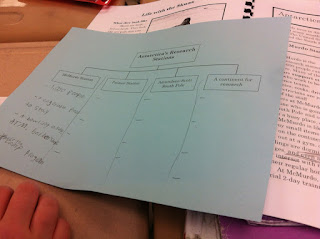

Readers often scan for specific words in a text. Simple vocabulary activities can be engaging and help students to become better at finding specific words. In the activity above, readers had to make predictions for how a word might be used in the text "Research Stations of Antarctica". Notice that I gave them the definitions.

Before they read, students had to make a prediction for how the words would be used. "Dormitories" was a word that they had learned in a previous text, so many predicted that the text would show that researchers or scientists sleep in dormitories in Antarctica. "Souvenirs" was a new word. Many students predicted that students would take rocks or ice back to their homes as souvenirs of Antarctica.

After reading, students went back to the text to find how the words were actually used. (I gave students the choice of whether to do this as they did their initial read, or whether they wanted to just read first and then look for the words; most students chose the latter.) Some of the words were in bold print, while others were not. It was fascinating to listen to them talking with each other about how to find the words! In some cases, they needed to read the sentence containing the word and the previous sentence to figure out how the word was used.

This activity is good for intermediate readers because there is a clear goal, and because they can judge their success (Did I find the word or not?) fairly easily. This provides a foundation of searching skills for students to use as they encounter more difficult tasks in text.

Other updates

Introduction to Text Structure: I've posted a new collection of text structure texts. This includes five texts about chinstrap penguins, five texts about peregrine falcons, and two assessments. My "Text Structure for Young Readers" PowerPoint is also included, along with a study guide that includes all of the texts in the PowerPoint.

Writing a Summary of Nonfiction: This PowerPoint is available free once more. (It is also included in Paraphrasing and Summarizing Lessons.) I took it down a few months ago in frustration at how my free things have been showing up re-posted under other people's names on docstoc and authorstream. However, I've gotten a few emails inquiring about it, so I'll give it another try. Case in point: My entire Understanding Text Structure PowerPoint is on Prezi, with new graphics, under someone else's name. Sigh.

Spelling: New spelling units are done. If I've been sending them to you, drop me a line at elkissn@yahoo.com and I'll send them your way.

How does this skill develop? Like summarizing, it's not something that we can just tell students to do. There are two main ways to help students learn to return to the text. The first way is to help them navigate through a text, so that they realize they can find answers efficiently. The second way is to give readers meaningful literal tasks that require them to return to the text.

Navigating a text

|

| This is the first page from a collection of Problem and Solution texts. |

After a first silent read of a text, I also like to have readers partner-read a text by sentence. Many struggling readers do not notice sentence and paragraph boundaries. When they read sentence-by-sentence, these boundaries matter! "Hey, it's my turn!" a partner will say indignantly.

What if you only have texts that don't have headings? Use different texts for instruction. For example, many popular Seymour Simon books have neither headings nor page numbers nor captions. These are fine to have in my classroom library, but not very useful for instruction. It takes a long time just to get everyone (literally) on the same page.

Finding words in a text

Readers often scan for specific words in a text. Simple vocabulary activities can be engaging and help students to become better at finding specific words. In the activity above, readers had to make predictions for how a word might be used in the text "Research Stations of Antarctica". Notice that I gave them the definitions.

Before they read, students had to make a prediction for how the words would be used. "Dormitories" was a word that they had learned in a previous text, so many predicted that the text would show that researchers or scientists sleep in dormitories in Antarctica. "Souvenirs" was a new word. Many students predicted that students would take rocks or ice back to their homes as souvenirs of Antarctica.

After reading, students went back to the text to find how the words were actually used. (I gave students the choice of whether to do this as they did their initial read, or whether they wanted to just read first and then look for the words; most students chose the latter.) Some of the words were in bold print, while others were not. It was fascinating to listen to them talking with each other about how to find the words! In some cases, they needed to read the sentence containing the word and the previous sentence to figure out how the word was used.

This activity is good for intermediate readers because there is a clear goal, and because they can judge their success (Did I find the word or not?) fairly easily. This provides a foundation of searching skills for students to use as they encounter more difficult tasks in text.

Other updates

Introduction to Text Structure: I've posted a new collection of text structure texts. This includes five texts about chinstrap penguins, five texts about peregrine falcons, and two assessments. My "Text Structure for Young Readers" PowerPoint is also included, along with a study guide that includes all of the texts in the PowerPoint.

Writing a Summary of Nonfiction: This PowerPoint is available free once more. (It is also included in Paraphrasing and Summarizing Lessons.) I took it down a few months ago in frustration at how my free things have been showing up re-posted under other people's names on docstoc and authorstream. However, I've gotten a few emails inquiring about it, so I'll give it another try. Case in point: My entire Understanding Text Structure PowerPoint is on Prezi, with new graphics, under someone else's name. Sigh.

Spelling: New spelling units are done. If I've been sending them to you, drop me a line at elkissn@yahoo.com and I'll send them your way.

Saturday, December 8, 2012

Finding Topics and Main Ideas

Kids have to be able to find topics and main ideas to understand nonfiction text. I look at these lessons as the foundation for all of our nonfiction work in the months to come. This week, I worked on topics and main ideas with several different groups of readers. Here are some thoughts on my experiences.

Do not: Assume that students already know how to find topics and main ideas in text

I've been teaching about this for more than a decade. Many kids are masters of skimming by when it comes to topic and main idea. They've learned to read the teacher, looking for the clues that you are subconsciously giving, instead of reading the text. I often resort to pretending that the text has a different topic to avoid giving these clues. Then the students have to convince me what the topic is!

Do: Look for repeated references in a text

To the adult reader, the topic of the text above just jumps right out: Weddell seals! But younger readers who are still reading word-for-word often do not take in the "whole view" of the text. For these readers, it's important to show them how to underline the repeated words in the text. We found every example of Weddell seal in the text above. As we did this, students saw quickly what the topic was.

Do: Look for multiple referents

Some texts, though, are tricky. Consider the text to the right. The topic, Southern elephant seals, is only mentioned once. The seals are referred to with the pronoun they and the referent these seals. Teaching topics with struggling readers is the perfect time to address multiple referents.

What did one of the readers suggest as the topic of this paragraph? Think about the way that struggling readers scan for words that they know. Yup--she said this paragraph was about elephants. On the one hand, this is a discouraging answer. On the other hand, it shows that she is trying to scan for a topic. She just needs more practice with going back to the text to refine her hypothesis.

Do: Have students work in pairs

Pairing students up to talk about their thinking is a great way to find out misconceptions. It's also a great way to find out new thinking tricks! My on- and above-grade level readers worked to sort cut-apart paragraphs. They had to read each sentence, and then determine the topic and the main idea. Listening in on the conversations was a fantastic way for me to hear what readers were thinking. For example, one pair was discarding the actual main idea sentences because they didn't sound "interesting" enough. (Main ideas often do sound boring, don't they? It's the details that are interesting.) This was a whole new way of looking at the task. I acknowledged their thinking, and then explained that main ideas often do sound boring. This helped them as they worked on their next paragraph.

In another group, I overheard a brilliant reader talking offhandedly as she sorted cards: "Detail, detail, detail, detail." When I asked her what she was doing, she said, "Well, first I just find the sentences that sound detail-y, the ones that have numbers and stuff. Those aren't going to be the main idea, so I set them aside." Again, this provided me with some insight about how students go about the task, and some good student language to use when helping struggling readers.

Do: Take it right back to text

I like to think of nonfiction instruction as following a whole-part-whole model. We look at a text and read it for an initial understanding. Then we look at a part--in this case, topics and main ideas. The next step is to take the idea back to the text.

For my struggling readers, I went right back to the familiar "Welcome to Antarctica" text that we had already read. We looked at the paragraphs and applied the same strategies to finding the topics and main ideas. Doing this with familiar text was helpful for them, as they could focus on the task instead of gaining an initial understanding.

For the other group of readers, we went right on to a new text, with the students applying the idea of topic and main idea to their work on a note-taking sheet. These readers thrive on novelty, so the challenge of a new text and a new concept really engaged them.

This is the first year that I have managed to pull together completely "united" activities, in that everything goes back to the Antarctica topic study we are doing this month. And I love it. The card match activity, the topics and main ideas paragraphs, and our core texts all reinforce one another, leading to great questions and use of vocabulary.

Additional Resources

Finding Topics and Main Ideas: Free Powerpoint from TeachersPayTeachers. (Note: My husband uses this, and always complains about the template that I used...one of these days I'll fix it up! The texts are good, and the sequence of instruction.)

Main Ideas and Details in Nonfiction Text: The Antarctica paragraphs are in here, along with many other items about supporting main ideas. A non-Antarctica version of the sorting sentences is included. (I'll get around to posting all of the Antarctica stuff eventually.)

Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Retelling: I learned a great deal about main ideas and topics as I researched this book. You'll find more on implicit main ideas, as well as research on how readers process main ideas.

Do not: Assume that students already know how to find topics and main ideas in text

I've been teaching about this for more than a decade. Many kids are masters of skimming by when it comes to topic and main idea. They've learned to read the teacher, looking for the clues that you are subconsciously giving, instead of reading the text. I often resort to pretending that the text has a different topic to avoid giving these clues. Then the students have to convince me what the topic is!

Do: Look for repeated references in a text

To the adult reader, the topic of the text above just jumps right out: Weddell seals! But younger readers who are still reading word-for-word often do not take in the "whole view" of the text. For these readers, it's important to show them how to underline the repeated words in the text. We found every example of Weddell seal in the text above. As we did this, students saw quickly what the topic was.

Do: Look for multiple referents

Some texts, though, are tricky. Consider the text to the right. The topic, Southern elephant seals, is only mentioned once. The seals are referred to with the pronoun they and the referent these seals. Teaching topics with struggling readers is the perfect time to address multiple referents.

What did one of the readers suggest as the topic of this paragraph? Think about the way that struggling readers scan for words that they know. Yup--she said this paragraph was about elephants. On the one hand, this is a discouraging answer. On the other hand, it shows that she is trying to scan for a topic. She just needs more practice with going back to the text to refine her hypothesis.

Do: Have students work in pairs

Pairing students up to talk about their thinking is a great way to find out misconceptions. It's also a great way to find out new thinking tricks! My on- and above-grade level readers worked to sort cut-apart paragraphs. They had to read each sentence, and then determine the topic and the main idea. Listening in on the conversations was a fantastic way for me to hear what readers were thinking. For example, one pair was discarding the actual main idea sentences because they didn't sound "interesting" enough. (Main ideas often do sound boring, don't they? It's the details that are interesting.) This was a whole new way of looking at the task. I acknowledged their thinking, and then explained that main ideas often do sound boring. This helped them as they worked on their next paragraph.

In another group, I overheard a brilliant reader talking offhandedly as she sorted cards: "Detail, detail, detail, detail." When I asked her what she was doing, she said, "Well, first I just find the sentences that sound detail-y, the ones that have numbers and stuff. Those aren't going to be the main idea, so I set them aside." Again, this provided me with some insight about how students go about the task, and some good student language to use when helping struggling readers.

Do: Take it right back to text

I like to think of nonfiction instruction as following a whole-part-whole model. We look at a text and read it for an initial understanding. Then we look at a part--in this case, topics and main ideas. The next step is to take the idea back to the text.

For my struggling readers, I went right back to the familiar "Welcome to Antarctica" text that we had already read. We looked at the paragraphs and applied the same strategies to finding the topics and main ideas. Doing this with familiar text was helpful for them, as they could focus on the task instead of gaining an initial understanding.

For the other group of readers, we went right on to a new text, with the students applying the idea of topic and main idea to their work on a note-taking sheet. These readers thrive on novelty, so the challenge of a new text and a new concept really engaged them.

This is the first year that I have managed to pull together completely "united" activities, in that everything goes back to the Antarctica topic study we are doing this month. And I love it. The card match activity, the topics and main ideas paragraphs, and our core texts all reinforce one another, leading to great questions and use of vocabulary.

Additional Resources

Finding Topics and Main Ideas: Free Powerpoint from TeachersPayTeachers. (Note: My husband uses this, and always complains about the template that I used...one of these days I'll fix it up! The texts are good, and the sequence of instruction.)

Main Ideas and Details in Nonfiction Text: The Antarctica paragraphs are in here, along with many other items about supporting main ideas. A non-Antarctica version of the sorting sentences is included. (I'll get around to posting all of the Antarctica stuff eventually.)

Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Retelling: I learned a great deal about main ideas and topics as I researched this book. You'll find more on implicit main ideas, as well as research on how readers process main ideas.

Sunday, December 2, 2012

Update on Spelling

Over the summer, I wrote about making a master word list and creating our own grade-level spelling list. We're now a few months into the project and I thought I'd take a moment to reflect on our progress.

The Master List

I started the master list last year. My goal was to create a list that could be filtered and arranged to find the absolute best words for vocabulary study. I took words from the Academic Word List, the Fry Words 200-500, the Common Core, and several other sources. Then, I gathered data on the words--how many syllables? What is the root? Is it a compound word? What syllable type is the first syllable? What phonograms does the word contain?

The result is an Excel spreadsheet of over 1,800 words. It's been useful for making spelling and vocabulary lists. For example, when I wanted to teach the root fin, I could quickly find important words that had the root. To teach words with long vowels, I looked under the open syllables category. (I am still sending out copies of the list if you'd like one.)

Our Fourth Grade Topics

We created a list of fourth grade spelling topics based on the Common Core and the Fountas and Pinnell Literacy Continuum. Here is an overview of the lists that we selected:

-Long/short vowel sound review

-Greek and Latin roots

-Silent letter combinations

-Contractions

-Homographs and homophones

-Multiple meaning words

-Synonyms and Antonyms

-Prefixes

-Noun forming suffixes

-Adjective forming suffixes

-Other suffixes

-Compound words

You'll notice that it's heavier on word meanings than spelling patterns. This is a tough issue. But with limited time for instruction, we decided to lean more heavily toward the vocabulary and look at spelling patterns as they fit into the words we selected.

To adjust for varying ability levels, we have two "tiers" within each list. Our words were selected from the Master Word List. The first tier includes words with more basic spellings. The second tier includes words that are more complex. Students are assigned a list based on their pretest score. Right now, we're at the silent letter combinations.

How it's going

We're moving along! It is a challenge for students. I'm glad to come back to self-corrected pretests, as I think that this is a really meaningful activity for students. I think that I have some of the old-fashioned country schoolma'am within me. I like the structure of a list, a set of homework activities, some carefully planned lessons, and a test. I think that there is some value to memorizing spelling words--as long as the words are carefully selected to be relevant and meaningful.

The Master List

I started the master list last year. My goal was to create a list that could be filtered and arranged to find the absolute best words for vocabulary study. I took words from the Academic Word List, the Fry Words 200-500, the Common Core, and several other sources. Then, I gathered data on the words--how many syllables? What is the root? Is it a compound word? What syllable type is the first syllable? What phonograms does the word contain?

The result is an Excel spreadsheet of over 1,800 words. It's been useful for making spelling and vocabulary lists. For example, when I wanted to teach the root fin, I could quickly find important words that had the root. To teach words with long vowels, I looked under the open syllables category. (I am still sending out copies of the list if you'd like one.)

Our Fourth Grade Topics

We created a list of fourth grade spelling topics based on the Common Core and the Fountas and Pinnell Literacy Continuum. Here is an overview of the lists that we selected:

-Long/short vowel sound review

-Greek and Latin roots

-Silent letter combinations

-Contractions

-Homographs and homophones

-Multiple meaning words

-Synonyms and Antonyms

-Prefixes

-Noun forming suffixes

-Adjective forming suffixes

-Other suffixes

-Compound words

You'll notice that it's heavier on word meanings than spelling patterns. This is a tough issue. But with limited time for instruction, we decided to lean more heavily toward the vocabulary and look at spelling patterns as they fit into the words we selected.

To adjust for varying ability levels, we have two "tiers" within each list. Our words were selected from the Master Word List. The first tier includes words with more basic spellings. The second tier includes words that are more complex. Students are assigned a list based on their pretest score. Right now, we're at the silent letter combinations.

How it's going

We're moving along! It is a challenge for students. I'm glad to come back to self-corrected pretests, as I think that this is a really meaningful activity for students. I think that I have some of the old-fashioned country schoolma'am within me. I like the structure of a list, a set of homework activities, some carefully planned lessons, and a test. I think that there is some value to memorizing spelling words--as long as the words are carefully selected to be relevant and meaningful.

Monday, November 26, 2012

Planning for a Nonfiction Topic Study

As I've watched my sons develop into readers, I noticed how they both started to delve deeply into a preferred topic in second grade. My older son read about airplanes and the physics of flight, while my younger son has read everything about cats. Watching these two readers has helped me to think about how topic knowledge is inextricably linked to reading skills. Their background knowledge about a topic helped them to attack and read increasingly more difficult texts.

It seems logical, then, that we should try to replicate this in our classrooms. But topic studies have gone in and out of style. When I started teaching (in the 90s! imagine!), thematic units were popular. But they weren't really structured. The idea--at least as it was communicated to my inexperienced teacher brain--was to gather as many resources as you could on a topic or theme, and then have students create some big project related to the theme.

As time passed and guided reading became popular, themes fell out of favor. Leveling was everything. I was told that trying to gather resources on a topic was useless. We'd never be able to afford to get every book at the levels we'd need, and it was far more important for kids to be reading texts at their levels than it was for them to study a topic. I got around this by starting to write my own texts, apologetically at first. But the more that I watched my own children become readers, the more I realized that seeing the same topics over and over was really important.

Now, topic studies are in style again. Yay! What I like about topic and theme studies as discussed in the Common Core is that they are to be structured with increasingly complex text. This mirrors what I see with Zachary and Aidan...the facts they learn from the easy text become necessary background knowledge to help them comprehend more complex text.

As I plan for this year's version of the Antarctica nonfiction unit, I've tried to be more conscious of how students are building their knowledge. I'm hoping to marry certain concepts about Antarctica with concepts about nonfiction. Here is the plan.

1. Choose your nonfiction skills to teach.

This year, I'm starting with paraphrasing. Then I'll move on to topics and main ideas, text features, and finally synthesizing. In the past, I did text features first. But this year I decided to change it because I want students to see how text features help to convey topics and main ideas.

2. Choose core texts.

I'm a weekly planner, so I choose texts for each week. At the beginning, I'm using some texts that I've written. This will help to build up the background knowledge that kids will need to get to the ideas in the more complex texts. But I'll also be using Trapped By the Ice, texts from Beyond Polar Bears and Penguins, and the LTER blog. As you choose texts, it's important to consider how ideas appear again and again. What are the most important concepts you want to wring from the topic? How are these concepts represented in texts?

3. Create a unit anticipation guide.

I love anticipation guides for a unit. Many details about Antarctica are counterintuitive--for example, the fact that polar bears don't eat penguins, and that summer and winter in the Southern Hemisphere are the opposite of here. The anticipation guide is a concrete way for learners to recognize what they have learned from reading and how their ideas have shifted. Presenting learners with opportunities to "rewire" their background knowledge is vital for learning. (For more information on this, see the research by Graham Nuthall...his articles have been so influential to me!)

4. Gather guided reading and auxiliary texts.

This process may take a few years. I pick up books wherever I can. It becomes a sort of "stone soup" situation--everyone working on the unit has a few things to contribute. Surprisingly, even texts that seem only tangentially related often offer kids some little gems of knowledge that they can weave into their schema.

5. Create a list of unit vocabulary.

This year I've started to be much more intentional with my vocabulary teaching. What words do kids need? Which words show up again and again? I do a weekly homework packet in my classroom, and I've included five vocabulary words (along with a related text) in each packet.

It all sounds like a great deal of work, and it is. But it is so worthwhile to hear kids sharing ideas and reflecting on what they've learned across texts. Whether topic studies are in style or not, they are a wonderful way to help students learn.

I'm hoping to put together what I've done with the Antarctica unit into a file. Until then, write to me if you would like any samples. (Please include your email address if you leave a comment! Otherwise, it's tough to figure out how to respond.)

It seems logical, then, that we should try to replicate this in our classrooms. But topic studies have gone in and out of style. When I started teaching (in the 90s! imagine!), thematic units were popular. But they weren't really structured. The idea--at least as it was communicated to my inexperienced teacher brain--was to gather as many resources as you could on a topic or theme, and then have students create some big project related to the theme.

As time passed and guided reading became popular, themes fell out of favor. Leveling was everything. I was told that trying to gather resources on a topic was useless. We'd never be able to afford to get every book at the levels we'd need, and it was far more important for kids to be reading texts at their levels than it was for them to study a topic. I got around this by starting to write my own texts, apologetically at first. But the more that I watched my own children become readers, the more I realized that seeing the same topics over and over was really important.

Now, topic studies are in style again. Yay! What I like about topic and theme studies as discussed in the Common Core is that they are to be structured with increasingly complex text. This mirrors what I see with Zachary and Aidan...the facts they learn from the easy text become necessary background knowledge to help them comprehend more complex text.

As I plan for this year's version of the Antarctica nonfiction unit, I've tried to be more conscious of how students are building their knowledge. I'm hoping to marry certain concepts about Antarctica with concepts about nonfiction. Here is the plan.

1. Choose your nonfiction skills to teach.

This year, I'm starting with paraphrasing. Then I'll move on to topics and main ideas, text features, and finally synthesizing. In the past, I did text features first. But this year I decided to change it because I want students to see how text features help to convey topics and main ideas.

2. Choose core texts.

I'm a weekly planner, so I choose texts for each week. At the beginning, I'm using some texts that I've written. This will help to build up the background knowledge that kids will need to get to the ideas in the more complex texts. But I'll also be using Trapped By the Ice, texts from Beyond Polar Bears and Penguins, and the LTER blog. As you choose texts, it's important to consider how ideas appear again and again. What are the most important concepts you want to wring from the topic? How are these concepts represented in texts?

3. Create a unit anticipation guide.

I love anticipation guides for a unit. Many details about Antarctica are counterintuitive--for example, the fact that polar bears don't eat penguins, and that summer and winter in the Southern Hemisphere are the opposite of here. The anticipation guide is a concrete way for learners to recognize what they have learned from reading and how their ideas have shifted. Presenting learners with opportunities to "rewire" their background knowledge is vital for learning. (For more information on this, see the research by Graham Nuthall...his articles have been so influential to me!)

4. Gather guided reading and auxiliary texts.

This process may take a few years. I pick up books wherever I can. It becomes a sort of "stone soup" situation--everyone working on the unit has a few things to contribute. Surprisingly, even texts that seem only tangentially related often offer kids some little gems of knowledge that they can weave into their schema.

5. Create a list of unit vocabulary.

This year I've started to be much more intentional with my vocabulary teaching. What words do kids need? Which words show up again and again? I do a weekly homework packet in my classroom, and I've included five vocabulary words (along with a related text) in each packet.

It all sounds like a great deal of work, and it is. But it is so worthwhile to hear kids sharing ideas and reflecting on what they've learned across texts. Whether topic studies are in style or not, they are a wonderful way to help students learn.

I'm hoping to put together what I've done with the Antarctica unit into a file. Until then, write to me if you would like any samples. (Please include your email address if you leave a comment! Otherwise, it's tough to figure out how to respond.)

Sunday, November 18, 2012

Comparing Texts with Pop-Up Books

Just as I like to work on summarizing throughout the year, I also like to work on comparing texts. Kids naturally enjoy finding connections between texts. If I model this early in the year, we can make strong connections all year long.

I decided to start with two quick pop-up books. The first reason for my choice was a practical one--I wanted really short texts that we could read in five minutes or less. But the second reason was a little deeper. I wanted to show students how even very short texts can communicate a theme in words and pictures.

Book 1: Beautiful Oops

This was an impulse purchase a few weeks ago...and it has now become a classroom favorite! As we read it, we talked about several details:

-The author's use of intentional mistakes

-The playful illustrations and bright colors

-The theme that is expressed

-How the text and pictures support the theme

Book 2: Big Frog Can't Fit In

Of course, my students love the books of Mo Willems, so this has already been passed around the classroom on free-reading Fridays. As we read this, we talked about:

-The problem and solution expressed in the book

-The use of pictures and pop-up elements

-The theme that is expressed

-How the text and pictures support the theme

After we read the books, we completed a chart to compare them, looking at the themes, the illustrations, and the text. One student added a new detail: "Both books show a problem that has to be solved!" When we used the chart to write a paragraph, I modeled starting with the heart of the comparison--why these books are being compared.

Beautiful Oops and Big Frog Can't Fit both express deep ideas through playful words and pictures.

Using my new Elmo wireless tablet (okay, it is really awesome to be able to write on the board from across the room!), we developed the rest of the paragraph by explaining how both books are similar and different. I made a big deal out of the phrase "on the other hand", talking about how sophisticated and grown-up it sounds. :)

After we did this together, students worked in clock buddy pairs to compare the books Molly's Pilgrim and Weslandia. At this point in the year, I give them a chart with criteria to consider. For these books, the criteria included the themes, how the characters are bullied, how the conflicts are resolved, and so forth. When students went to write their paragraphs, they chose the details from the chart that they wanted to develop. As a result, every pair's paragraph had a different focus. But most were solid and interesting, not bad for early in the fourth grade year! (Ten groups did experiment with "on the other hand", showing me that making a big deal out of the phrase must have made an impact.)

Pop-up books often don't have much of a place in intermediate classrooms...but these books are so engaging that they can really be useful tools.

I decided to start with two quick pop-up books. The first reason for my choice was a practical one--I wanted really short texts that we could read in five minutes or less. But the second reason was a little deeper. I wanted to show students how even very short texts can communicate a theme in words and pictures.

Book 1: Beautiful Oops

This was an impulse purchase a few weeks ago...and it has now become a classroom favorite! As we read it, we talked about several details:

-The author's use of intentional mistakes

-The playful illustrations and bright colors

-The theme that is expressed

-How the text and pictures support the theme

Book 2: Big Frog Can't Fit In

Of course, my students love the books of Mo Willems, so this has already been passed around the classroom on free-reading Fridays. As we read this, we talked about:

-The problem and solution expressed in the book

-The use of pictures and pop-up elements

-The theme that is expressed

-How the text and pictures support the theme

After we read the books, we completed a chart to compare them, looking at the themes, the illustrations, and the text. One student added a new detail: "Both books show a problem that has to be solved!" When we used the chart to write a paragraph, I modeled starting with the heart of the comparison--why these books are being compared.

Beautiful Oops and Big Frog Can't Fit both express deep ideas through playful words and pictures.

Using my new Elmo wireless tablet (okay, it is really awesome to be able to write on the board from across the room!), we developed the rest of the paragraph by explaining how both books are similar and different. I made a big deal out of the phrase "on the other hand", talking about how sophisticated and grown-up it sounds. :)

After we did this together, students worked in clock buddy pairs to compare the books Molly's Pilgrim and Weslandia. At this point in the year, I give them a chart with criteria to consider. For these books, the criteria included the themes, how the characters are bullied, how the conflicts are resolved, and so forth. When students went to write their paragraphs, they chose the details from the chart that they wanted to develop. As a result, every pair's paragraph had a different focus. But most were solid and interesting, not bad for early in the fourth grade year! (Ten groups did experiment with "on the other hand", showing me that making a big deal out of the phrase must have made an impact.)

Pop-up books often don't have much of a place in intermediate classrooms...but these books are so engaging that they can really be useful tools.

Tuesday, November 13, 2012

Teaching Point of View

Find classroom-ready materials for teaching point of view: Point of View Stories and Activities

Point of view is now a fourth grade skill! Hooray!

Cheering was not actually my first instinct. But I've taught point of view to fourth graders over the past three weeks, and I've learned that it is not actually as hard as I feared it might be. Here are some hints to get started.

Start concrete

When I taught point of view in sixth and seventh grades, I could jump quickly into the abstract. We went right into looking at texts and writing them from different points of view.

With my fourth graders, though, I knew that I needed something more concrete. Enter the basket of stuffed animals! I started with the class favorite, Larry the Lobster, and wrote two sentences:

I live in the ocean.

Larry lives in the ocean.

I asked students, "How are these sentences different?" They could see that the sentences were written differently, and grasped at how to verbalize the difference. Then, I showed two more sentences on index cards:

He eats crustaceans.

I eat crustaceans.

I called on students to categorize the cards. Which ones were the most similar? Why? It was only after they could explain the difference between who was narrating the action that I introduced the terms first person and third person.

Next, students chose stuffed animals for writing buddies. On white boards, they tried writing two sentences about their stuffed animals--one in first person, and one in third person. Once I looked over their sentences, they recopied them onto index cards. We regrouped and took turns classifying each student's sentence and guessing which stuffed animal was the star of the sentence.

Read and share

Once students had an initial understanding of point of view, we had a huge storm. We were out of school for two days and then spent two days in classes at the high school--how exciting! Our school did not have electricity, but the other schools in the district did. The teachers were wonderfully accommodating and the students were great.

The best part about being in the high school was the high school helpers! I have three students who come up to my school to volunteer in the afternoons. When we were at the high school, they came to our temporary room during their free periods to help out. (Did I mention that they are awesome?)

I split my reading class into three so that students could hear read alouds from each point of view. Luckily I had been planning to do a presentation before the hurricane interfered, so my suitcase was filled with books. I needed short, easy books that high schoolers could quickly read aloud.

Shortcut by Donald Crews is one of my favorite go-to books for teaching so many different ideas. Personal narratives, intertextual connections, suspense, use of long and short sentences....and now point of view!

Mr. Gumpy's Outing by John Burningham was a good choice of a third person book--short, easy, and clearly third person.

It's tempting to leave out second person. "No one uses it much," I've heard teachers say. But if you're taking the time to deal with first person and third person, second person is not that tough. Besides, kids love second person. It's the language of the Choose Your Own Adventure and Interactive History books! During our rotations, I read the second person book, choosing excerpts from the Underground Railroad Interactive History. We talked about why authors might choose second person, but why some readers really resist reading texts that are written this way.

While these short read alouds weren't what I originally planned, they worked out wonderfully to teach reading in an unfamiliar classroom in an unfamiliar school.

Deal with dialogue

Once we returned to our own school, with the excitement of our adventures behind us, we continued our study of point of view. A card match activity was fun--students received cards with pieces of a story in either first person or third person, and had to find the student with the corresponding card.

Dialogue continues to be a challenge for students. Often, students will see text like this:

"I can help paint!" Ben said excitedly.

Students see that word I in the dialogue and say that the story is in first person. In these cases, I ask students: Who is telling the story? Is the narrator a character in the story? I try to lead them to think about what the story is really saying. Then, if they are still confused, I just say---"When we talk about point of view, don't pay attention to the dialogue. Look for what's happening outside the dialogue." And sometimes this works.

Materials

I'm working on putting together some materials for teaching point of view in the intermediate grades. So much of what I found is geared toward middle school students! If you would like some materials, write me an email. (Again!)

Point of view is now a fourth grade skill! Hooray!

Cheering was not actually my first instinct. But I've taught point of view to fourth graders over the past three weeks, and I've learned that it is not actually as hard as I feared it might be. Here are some hints to get started.

Start concrete

When I taught point of view in sixth and seventh grades, I could jump quickly into the abstract. We went right into looking at texts and writing them from different points of view.

With my fourth graders, though, I knew that I needed something more concrete. Enter the basket of stuffed animals! I started with the class favorite, Larry the Lobster, and wrote two sentences:

I live in the ocean.

Larry lives in the ocean.

I asked students, "How are these sentences different?" They could see that the sentences were written differently, and grasped at how to verbalize the difference. Then, I showed two more sentences on index cards:

He eats crustaceans.

I eat crustaceans.

I called on students to categorize the cards. Which ones were the most similar? Why? It was only after they could explain the difference between who was narrating the action that I introduced the terms first person and third person.

Next, students chose stuffed animals for writing buddies. On white boards, they tried writing two sentences about their stuffed animals--one in first person, and one in third person. Once I looked over their sentences, they recopied them onto index cards. We regrouped and took turns classifying each student's sentence and guessing which stuffed animal was the star of the sentence.

Read and share

Once students had an initial understanding of point of view, we had a huge storm. We were out of school for two days and then spent two days in classes at the high school--how exciting! Our school did not have electricity, but the other schools in the district did. The teachers were wonderfully accommodating and the students were great.

The best part about being in the high school was the high school helpers! I have three students who come up to my school to volunteer in the afternoons. When we were at the high school, they came to our temporary room during their free periods to help out. (Did I mention that they are awesome?)

I split my reading class into three so that students could hear read alouds from each point of view. Luckily I had been planning to do a presentation before the hurricane interfered, so my suitcase was filled with books. I needed short, easy books that high schoolers could quickly read aloud.

Shortcut by Donald Crews is one of my favorite go-to books for teaching so many different ideas. Personal narratives, intertextual connections, suspense, use of long and short sentences....and now point of view!

Mr. Gumpy's Outing by John Burningham was a good choice of a third person book--short, easy, and clearly third person.

It's tempting to leave out second person. "No one uses it much," I've heard teachers say. But if you're taking the time to deal with first person and third person, second person is not that tough. Besides, kids love second person. It's the language of the Choose Your Own Adventure and Interactive History books! During our rotations, I read the second person book, choosing excerpts from the Underground Railroad Interactive History. We talked about why authors might choose second person, but why some readers really resist reading texts that are written this way.

While these short read alouds weren't what I originally planned, they worked out wonderfully to teach reading in an unfamiliar classroom in an unfamiliar school.

Deal with dialogue

Once we returned to our own school, with the excitement of our adventures behind us, we continued our study of point of view. A card match activity was fun--students received cards with pieces of a story in either first person or third person, and had to find the student with the corresponding card.

Dialogue continues to be a challenge for students. Often, students will see text like this:

"I can help paint!" Ben said excitedly.

Students see that word I in the dialogue and say that the story is in first person. In these cases, I ask students: Who is telling the story? Is the narrator a character in the story? I try to lead them to think about what the story is really saying. Then, if they are still confused, I just say---"When we talk about point of view, don't pay attention to the dialogue. Look for what's happening outside the dialogue." And sometimes this works.

Materials

I'm working on putting together some materials for teaching point of view in the intermediate grades. So much of what I found is geared toward middle school students! If you would like some materials, write me an email. (Again!)

Friday, October 26, 2012

Story Synthesis: Best Activity Ever!

There are some activities that transcend classrooms, ages, and ability levels. These are the golden activities that have big ideas that can be explored and examined again and again. Even better are the amazing activities that don't require a great deal of preparation.

The Story Synthesis is one of those activities. It's very simple--I learned about it from a kindergarten teacher. But I've done it again and again, with different groups of students, and it never fails to captivate and engage them.

The basic idea

Split the class into groups. One half of the class creates characters, and one half creates settings. They do this apart from one another, preferably in secret. (If you say that something is "Top Secret", it instantly becomes alluring and exciting!) Then, they get together. They have to introduce the characters to the setting and create a story. What kind of conflict could arise from this situation?

This year's version

This year, I had students work in pairs to create either settings or characters. We kept the characters hidden in envelopes over the several days that it took us to create them. The settings were on large pieces of poster board and were kept in a drawer.

After students worked on either characters or settings, it was time for them to get together! I had made the groups several weeks ago (and I still had the paper that I had written them down on!), so even I was surprised at how things turned out. There were laughs and groans as the groups were created. Two girls who worked on SuperDog and Hero Fairy (best character ever!) were paired with an underwater setting. The "army guy medics" were sent to a medieval castle.

Exploring conflict and character

And this led to some interesting conversations. What kind of conflict could occur with SuperDog and Hero Fairy? How would the underwater setting affect the conflict? Which character was the protagonist? How could the conflict in the story be classified? This year, I did make a quick little sheet to give students some guidance as they worked to answer these questions. But the activity could easily be scaled down for younger students.

Playing the story

After students fleshed out the basics of their story (and learned a great deal about compromise in the bargain), they got to use the characters to act out the story in the setting. The final step, which we haven't done yet, is to write it out.

I love this activity because it gets kids quickly to deep thinking about stories. How do characters and settings interact? How does the conflict relate to both? It gets them saying vocabulary words ("The protagonist should be...." "Medusa is the villain!"..."Mrs. Kissner, I forget. What does the present mean again?") and working with each other.

Best of all, though, is how much they enjoy it! It makes a good fun activity to sprinkle throughout our stamina-building quiet reading and rigorous Common Core activities. :)

The Story Synthesis is one of those activities. It's very simple--I learned about it from a kindergarten teacher. But I've done it again and again, with different groups of students, and it never fails to captivate and engage them.

The basic idea

Split the class into groups. One half of the class creates characters, and one half creates settings. They do this apart from one another, preferably in secret. (If you say that something is "Top Secret", it instantly becomes alluring and exciting!) Then, they get together. They have to introduce the characters to the setting and create a story. What kind of conflict could arise from this situation?

This year's version

This year, I had students work in pairs to create either settings or characters. We kept the characters hidden in envelopes over the several days that it took us to create them. The settings were on large pieces of poster board and were kept in a drawer.

After students worked on either characters or settings, it was time for them to get together! I had made the groups several weeks ago (and I still had the paper that I had written them down on!), so even I was surprised at how things turned out. There were laughs and groans as the groups were created. Two girls who worked on SuperDog and Hero Fairy (best character ever!) were paired with an underwater setting. The "army guy medics" were sent to a medieval castle.

Exploring conflict and character

And this led to some interesting conversations. What kind of conflict could occur with SuperDog and Hero Fairy? How would the underwater setting affect the conflict? Which character was the protagonist? How could the conflict in the story be classified? This year, I did make a quick little sheet to give students some guidance as they worked to answer these questions. But the activity could easily be scaled down for younger students.

Playing the story

After students fleshed out the basics of their story (and learned a great deal about compromise in the bargain), they got to use the characters to act out the story in the setting. The final step, which we haven't done yet, is to write it out.

I love this activity because it gets kids quickly to deep thinking about stories. How do characters and settings interact? How does the conflict relate to both? It gets them saying vocabulary words ("The protagonist should be...." "Medusa is the villain!"..."Mrs. Kissner, I forget. What does the present mean again?") and working with each other.

Best of all, though, is how much they enjoy it! It makes a good fun activity to sprinkle throughout our stamina-building quiet reading and rigorous Common Core activities. :)

Sunday, October 21, 2012

Core Reading with Struggling Readers

Early October brings a mix of emotions in the classroom. On the one hand, there is the elation of feeling that we have finally come together as a class. The mix of personalities has settled into a cohesive culture with its own inside jokes, traditions, and routines. (My class this year has taken to making up imaginary students to sit at the empty desks, complete with name labels and supposed personalities. And they have taken on the stuffed toy lobster, which has sat unnoticed on the shelf for years, as a special mascot. I just love to watch these things happen.)

But by early October, I also have a very clear picture of the task that I must accomplish by the end of the year. Looking at the DRA scores of my struggling readers, it was easy to feel daunted by the expectations of the Common Core to get these readers into grade-level reading selections. "How can I do this?" I asked my husband. "How can I get someone at a DRA 18 into a level 40 book?"

My husband, who teaches third grade, was a little calmer than I was. He also has a longer memory. He said, "Didn't you write a whole chapter about that in your book?"

"But it's--" I started, ready to argue, and then I stopped because I realized that he was right. There it was, in The Forest and the Trees, a long section about giving different kinds of support to readers as they work with grade level text. Right.

So I do know how to do this, I thought. As I planned for the upcoming weeks of instruction, I considered my readers carefully. The notion of before, during, and after has helped me to frame my lessons.

Before Reading: Building Automaticity

To build automaticity with the words in the grade level text, I've been making speed drills, flash cards, and word sorts. These look different depending on the text and the groups.

For Weslandia, I pulled out one and two-syllable words. One group focused on the one-syllable words. Words like loom, built, and wove are a real challenge for them. With another group, I worked on syllabication strategies. We worked on words from the text like civilization, innovation, and devise. With each of these lessons, I focused on using a decoding strategy that wouldn't just help students with words from this text, but would help them to decode words in future texts as well.

For Molly's Pilgrim, I pulled out all of the compound words. I made cards by separating them (school/yard) and then we put them back together. In this case, I focused on understanding the compound words. Many students had never heard of a "schoolyard" before, so we talked about making sense of the compound word by putting together the meanings of the other words. I included some other words on the speed drill as well, organized by the number of syllables, so that it was easy to listen to tailor the list for different readers and listen to them read the words over multiple days.

With each of these activities, I also used the words that we practiced to build predictions for the text. "In the text we'll read next week, Molly has trouble reading the word Thanksgiving. Why do you think this might be?" Then we shared our thoughts about why this might happen in the story.

Before Reading: Building Background

It's also important to build background knowledge for all readers. While we were working with Weslandia, I wrote a short little passage about the Roman civilization for students to read as their homework fluency practice. This passage got them to say the word "civilization" repeatedly throughout the week. Because we are also starting our study of Greek and Latin roots, this text built some instant connections between our reading and word study.

During Reading: Strong Sustaining Strategies

I am also working this year to give every reader the chance to independently interact with grade level or approaching grade level text. To make this successful, I have to think very carefully about the sustaining strategies that they will use. Where will they have difficulty? What can I do to support them?

The syllabication strategies we practiced before reading become very important here, as readers have to try to figure out words on their own. This goes hand in hand with the "clicks and clunks" that we've already practiced. Identifying where meaning breaks down is a necessary step to better comprehension. If struggling readers aren't aware of what difficulties they are having, they can't utilize better strategies! After we spend time reading silently, we can talk about where those clunks occurred and how we can fix them.

During Reading: Embedded Questions and Reading Road Maps

I also like to use these activities to help readers make meaning in a text. Embedded questions are simply questions that you insert into the main body of the text. They are a wonderful scaffold for helping readers to make inferences as they read. Think about the key ideas that a reader will need to gather from a section, and then write a question that cues them to think about those ideas.

Reading road maps are similar. They are based in the idea that reading is like a journey. Sometimes they are organized as before, during, and after, as this example. I've stopped trying to make mine "cute" and use a simple table design.

After Reading: Notebook Resources

After students have read the text and we've talked about our clicks and clunks, we go deeper into analyzing the story. Struggling readers and ELL students really benefit from having a notebook full of resources to help them answer questions.

For example, consider character traits. A question might ask, "What trait of the main character helps her to resolve the conflict?" A student who needs help in reading will benefit tremendously from having a list of character traits to refer to while answering this question. This list will help the reader to be able to focus on gathering the text details to support an answer to this question. Lists of themes work in the same way. When a reader has a list of universal themes to refer to, identifying and supporting a theme becomes a much easier task.

Getting students who are reading significantly below grade level to comprehend grade level text is a tough task. By planning scaffolding before, during, and after reading, I can help to make the task a little easier.

A note on materials: I've created several Common Core friendly materials for Weslandia and Molly's Pilgrim...if you would like any, please write to me or leave a comment. (Make sure that you put your email address in the comment! If you don't, I don't have any way to reach you. )

But by early October, I also have a very clear picture of the task that I must accomplish by the end of the year. Looking at the DRA scores of my struggling readers, it was easy to feel daunted by the expectations of the Common Core to get these readers into grade-level reading selections. "How can I do this?" I asked my husband. "How can I get someone at a DRA 18 into a level 40 book?"

My husband, who teaches third grade, was a little calmer than I was. He also has a longer memory. He said, "Didn't you write a whole chapter about that in your book?"

"But it's--" I started, ready to argue, and then I stopped because I realized that he was right. There it was, in The Forest and the Trees, a long section about giving different kinds of support to readers as they work with grade level text. Right.

So I do know how to do this, I thought. As I planned for the upcoming weeks of instruction, I considered my readers carefully. The notion of before, during, and after has helped me to frame my lessons.

Before Reading: Building Automaticity

To build automaticity with the words in the grade level text, I've been making speed drills, flash cards, and word sorts. These look different depending on the text and the groups.

For Weslandia, I pulled out one and two-syllable words. One group focused on the one-syllable words. Words like loom, built, and wove are a real challenge for them. With another group, I worked on syllabication strategies. We worked on words from the text like civilization, innovation, and devise. With each of these lessons, I focused on using a decoding strategy that wouldn't just help students with words from this text, but would help them to decode words in future texts as well.

For Molly's Pilgrim, I pulled out all of the compound words. I made cards by separating them (school/yard) and then we put them back together. In this case, I focused on understanding the compound words. Many students had never heard of a "schoolyard" before, so we talked about making sense of the compound word by putting together the meanings of the other words. I included some other words on the speed drill as well, organized by the number of syllables, so that it was easy to listen to tailor the list for different readers and listen to them read the words over multiple days.

With each of these activities, I also used the words that we practiced to build predictions for the text. "In the text we'll read next week, Molly has trouble reading the word Thanksgiving. Why do you think this might be?" Then we shared our thoughts about why this might happen in the story.

Before Reading: Building Background

It's also important to build background knowledge for all readers. While we were working with Weslandia, I wrote a short little passage about the Roman civilization for students to read as their homework fluency practice. This passage got them to say the word "civilization" repeatedly throughout the week. Because we are also starting our study of Greek and Latin roots, this text built some instant connections between our reading and word study.

During Reading: Strong Sustaining Strategies

I am also working this year to give every reader the chance to independently interact with grade level or approaching grade level text. To make this successful, I have to think very carefully about the sustaining strategies that they will use. Where will they have difficulty? What can I do to support them?

The syllabication strategies we practiced before reading become very important here, as readers have to try to figure out words on their own. This goes hand in hand with the "clicks and clunks" that we've already practiced. Identifying where meaning breaks down is a necessary step to better comprehension. If struggling readers aren't aware of what difficulties they are having, they can't utilize better strategies! After we spend time reading silently, we can talk about where those clunks occurred and how we can fix them.

During Reading: Embedded Questions and Reading Road Maps

I also like to use these activities to help readers make meaning in a text. Embedded questions are simply questions that you insert into the main body of the text. They are a wonderful scaffold for helping readers to make inferences as they read. Think about the key ideas that a reader will need to gather from a section, and then write a question that cues them to think about those ideas.

Reading road maps are similar. They are based in the idea that reading is like a journey. Sometimes they are organized as before, during, and after, as this example. I've stopped trying to make mine "cute" and use a simple table design.

After Reading: Notebook Resources

After students have read the text and we've talked about our clicks and clunks, we go deeper into analyzing the story. Struggling readers and ELL students really benefit from having a notebook full of resources to help them answer questions.

For example, consider character traits. A question might ask, "What trait of the main character helps her to resolve the conflict?" A student who needs help in reading will benefit tremendously from having a list of character traits to refer to while answering this question. This list will help the reader to be able to focus on gathering the text details to support an answer to this question. Lists of themes work in the same way. When a reader has a list of universal themes to refer to, identifying and supporting a theme becomes a much easier task.

Getting students who are reading significantly below grade level to comprehend grade level text is a tough task. By planning scaffolding before, during, and after reading, I can help to make the task a little easier.

A note on materials: I've created several Common Core friendly materials for Weslandia and Molly's Pilgrim...if you would like any, please write to me or leave a comment. (Make sure that you put your email address in the comment! If you don't, I don't have any way to reach you. )

Tuesday, October 9, 2012

Three ways to improve student summaries

Earlier this week I had the pleasure of pulling out my presentation suitcases and doing a presentation about summarizing. I've been presenting on this topic for about five years now, but each time is new and interesting. There are just so many nuances to teaching summarizing, so many things to consider as I try to find that right match between reader and task.

I decided to structure the presentation in a new way this time, looking at several ways that classroom teachers can easily build summarizing skills in students. Here are three that work well for me in my classroom.

Retelling

I love retelling as an instructional strategy for any grade level. For students who seem to be having trouble remembering information from a text, retelling with a partner can be a good place to begin. I especially like having students use pictures or props to retell a text.

Don't neglect retelling nonfiction. Here are some simple directions that I give to students as they retell nonfiction.

Written paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is simply restating an author's words in a new way. This can be a difficult task for students who lack a wide bank of vocabulary words. Working with shorter pieces of text helps to build these skills a little at a time.

I like to project a page or a paragraph from a text and have students paraphrase the events or the information. This is pretty quick, and it lets us talk about the challenges that the text poses. What lists do we need to collapse? How can we find other ways to arrange the sentences? Besides helping students to improve their summarizing skills, paraphrasing parts of texts will also help students to put together text evidence to support their answers to open-ended questions.

(More specifics can be found in my paraphrasing and summarizing unit or in the book Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Retelling)

Scaffolded summaries

A scaffolded summary is like a writing frame. The teacher provides part of the writing, and the students provide the rest. Scaffolded summaries can offer more or less support, depending on student needs. Here is a highly supportive summary that I gave to students as a first step into summarizing. Notice that I combined the summarizing task with a vocabulary task, putting a word bank at the top of the page. (The text is from the fourth grade Fluency Formula book.)

With a highly supportive scaffolded summary, it's important to keep the task from becoming just a fill in the blanks activity. Doing a choral reading of the entire summary can help kids to hear the academic language. (In my classroom, kids like alternating reading with boys reading one sentence, and girls the next. They also enjoy "reading like spies"--reading aloud as if every sentence ends in a deep, dark secret.)

Another way to make this an engaging task is to show students a summary with wrong answers filled in. Why are they wrong? What details from the text can show this?

As students become more skilled in summarizing, the frame can offer less and less support. Here is a scaffolded summary frame for students to use as they summarize chronological order nonfiction text. Notice that this frame is not text-specific, but can be used with any text that goes along with this text structure. (This frame is included in my text structure unit on chronological order. Frames like this are included in all of the other text structure units as well.)

Teaching students to summarize is hard. The most important thing to keep in mind, however, is that summarizing must be revisited again and again. It can't be a single unit that you teach once and then put aside. Instead, students need to see summarizing activities with every text. Whether you are retelling, paraphrasing parts of text, or using a scaffolded summary, ongoing activities will help your students to be successful.

I decided to structure the presentation in a new way this time, looking at several ways that classroom teachers can easily build summarizing skills in students. Here are three that work well for me in my classroom.

Retelling

I love retelling as an instructional strategy for any grade level. For students who seem to be having trouble remembering information from a text, retelling with a partner can be a good place to begin. I especially like having students use pictures or props to retell a text.

Don't neglect retelling nonfiction. Here are some simple directions that I give to students as they retell nonfiction.

Written paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is simply restating an author's words in a new way. This can be a difficult task for students who lack a wide bank of vocabulary words. Working with shorter pieces of text helps to build these skills a little at a time.

I like to project a page or a paragraph from a text and have students paraphrase the events or the information. This is pretty quick, and it lets us talk about the challenges that the text poses. What lists do we need to collapse? How can we find other ways to arrange the sentences? Besides helping students to improve their summarizing skills, paraphrasing parts of texts will also help students to put together text evidence to support their answers to open-ended questions.

(More specifics can be found in my paraphrasing and summarizing unit or in the book Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Retelling)

Scaffolded summaries

A scaffolded summary is like a writing frame. The teacher provides part of the writing, and the students provide the rest. Scaffolded summaries can offer more or less support, depending on student needs. Here is a highly supportive summary that I gave to students as a first step into summarizing. Notice that I combined the summarizing task with a vocabulary task, putting a word bank at the top of the page. (The text is from the fourth grade Fluency Formula book.)

With a highly supportive scaffolded summary, it's important to keep the task from becoming just a fill in the blanks activity. Doing a choral reading of the entire summary can help kids to hear the academic language. (In my classroom, kids like alternating reading with boys reading one sentence, and girls the next. They also enjoy "reading like spies"--reading aloud as if every sentence ends in a deep, dark secret.)

Another way to make this an engaging task is to show students a summary with wrong answers filled in. Why are they wrong? What details from the text can show this?

As students become more skilled in summarizing, the frame can offer less and less support. Here is a scaffolded summary frame for students to use as they summarize chronological order nonfiction text. Notice that this frame is not text-specific, but can be used with any text that goes along with this text structure. (This frame is included in my text structure unit on chronological order. Frames like this are included in all of the other text structure units as well.)

Teaching students to summarize is hard. The most important thing to keep in mind, however, is that summarizing must be revisited again and again. It can't be a single unit that you teach once and then put aside. Instead, students need to see summarizing activities with every text. Whether you are retelling, paraphrasing parts of text, or using a scaffolded summary, ongoing activities will help your students to be successful.

Labels:

common core,

paraphrasing,

retelling,

summarizing

Monday, October 1, 2012

One hour, three people, four groups: Making co-teaching work

Right now, we've come up with a very workable arrangement for our co-teaching class. It's a model that works well and limits the number of transitions. This arrangement needs one hour in which 3 people are available to share a class. Right now, it works wonderfully because I have a student teacher. Later in the school year...well, I won't worry about that for now.

One of my problems with the standard model of guided reading is the amount of time that students spend left to their own devices. There are many students who can manage this, and succeed very well. However, for struggling readers, forty-five minutes of independent work can leave them spinning their wheels instead of moving forward.

Last year, when there were three of us working with one class, we tried using three sessions. But this led to too many transitions. Parallel teaching, in which the same lessons are delivered in different groups, left us feeling even more fragmented. We wanted some feeling of together-ness, that feeling of "our class" and not "my group, your group."

So we came up with this arrangement. It works well and targets support at the kids who really need it.

Divide the class into four groups.

We used a combination of assessment tools to do this. We've come up with two groups that are intensive and two groups that are strategic. For the sake of discussion, let's call the groups North, South, East, and West.

Begin the class with independent reading.

With kids arriving from different classes, it's important to have a calm, quiet routine for the start of class. We use the 10 minutes at the start to share information and (when all is well) listen in on readers and maintain a robust independent reading program.

The hour block is broken into 2 sessions.

Teacher A: One teacher devotes planning and instruction to core instruction. This teacher creates a half-hour lesson to present two times during the hour long block--once to groups North and East, and once to groups South and West. This lesson is focused on using grade level text and grade level curriculum. With only 12-15 kids in the session, Teacher A can focus on really working deeply with the core text and grade level activities. When I teach the core, I have kids sitting on the carpet with clipboards, pencils, and partners.

Teacher B: This teacher alternates between seeing North and South on one day, and East and West on the other. This teacher focuses on guided reading with leveled text at the groups' instructional levels.

Teacher C: This third teacher could follow two pathways. In one scenario, Teachers B and C would both run guided reading groups, enabling all readers to have guided reading every day. In the other scenario (which we are using right now), Teacher C does word work related to the core reading selection. I'll be Teacher C in the next few weeks. Our phonics and fluency screenings show that our kids need intensive work on word recognition and multisyllabic words. I'm going to work on these topics using words and sentences that I am pulling from our grade level core texts. I'll work a few days ahead, giving kids the word background they need to be more successful with the grade level text.

Meet up again for the last 5 minutes

After the 60-minute block, kids return to my classroom. This regrouping time really is just our chance to make sure that folders are returned, books are put away, and so forth. I like to put up something fun on the Promethean board during this time--lately the kids have been loving the Scholastic book trailers available here. Sometimes I show YouTube videos related to our core reading selection. I keep this time relaxed and light-hearted to end on a high note every day.

Don't do this every day

I hate teaching plans that require superhuman concentration and stamina. When I get that breathless, overwhelmed feeling, I know that I'm not being as effective as I can be. On one day out of the cycle, we go to the computer lab for Study Island games and other computer-based practice. This gives us a chance to do progress monitoring and assessments without sacrificing instruction. We can also sit together for a few minutes in the lab to share student work and make plans for the next cycle.

Other notes